Meet Our Faculty: In this Rutgers Global Health Institute content series, we highlight our core faculty members.

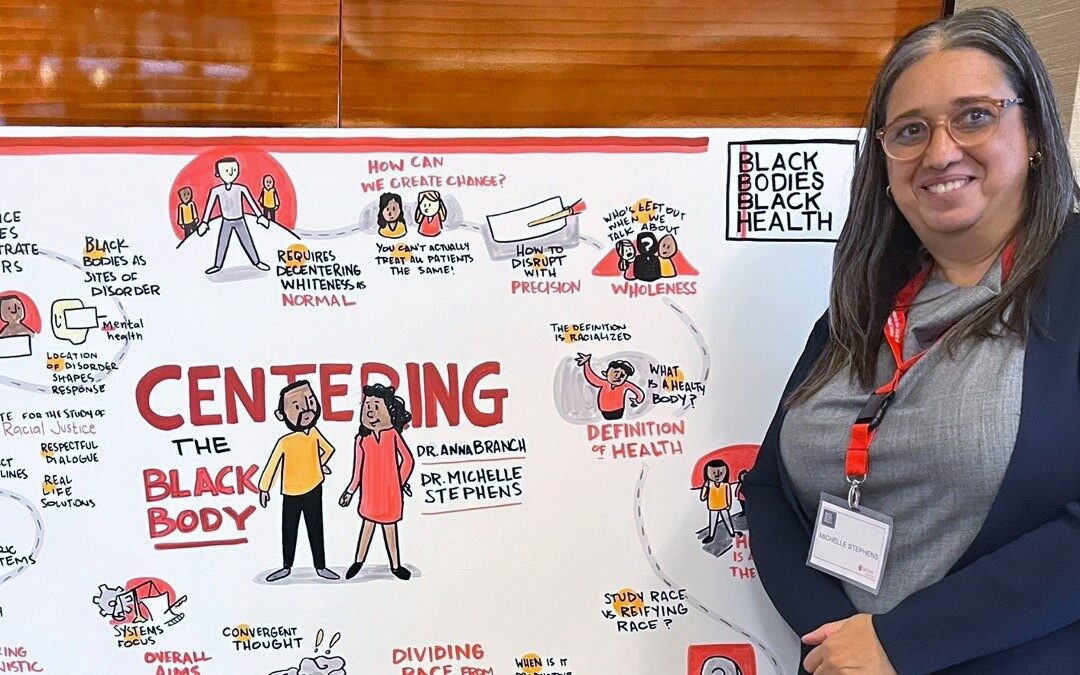

She may not have realized it at the time, but Michelle Stephens’s apparently disparate professional roles – as the dean of humanities at Rutgers’ School of Arts and Sciences and as a psychoanalyst – placed her perfectly to create a major scholarly initiative examining the interplay between race and health. That endeavor, Black Bodies, Black Health, is a signature project of the Institute for the Study of Global Racial Justice, founded at Rutgers in 2020 by Stephens, who also serves as its executive director.

“As a trained psychoanalyst,” says Stephens, who became a core faculty member of Rutgers Global Health Institute in 2022, “I’ve worked on a number of initiatives having to do with race, mental health, and psychic wellbeing, and on the relationship between individuals’ health – both psychological and physiological – and the broader cultural and social contexts within which they live.” Now, through this universitywide and highly collaborative institute and the Black Bodies, Black Health project, in particular, Stephens is bringing new energy to critical studies of the connections between structural racism and health outcomes.

Other Rutgers Roles

- Professor, Department of English and Department of Latino and Caribbean Studies, School of Arts and Sciences, Rutgers University–New Brunswick

- Affiliate Faculty, Program in Comparative Literature, School of Arts and Sciences

Asking Why and How

Growing up in Jamaica, West Indies, Stephens was an avid reader of fiction with a passion to understand why people acted as they did – a fascination that’s stayed with her.

“I enjoy being very reflective about what motivates people,” she says. That desire to understand how people think, coupled with her love of novels, led her to a college major in the humanities, which is an academic discipline focused on the expression of the human spirit through fields like literature, art, and philosophy. Eventually, it also led her to become an educator. “I wanted to be a teacher because I enjoyed talking about how books can be a window into how we relate to each other as human beings,” she says. It also propelled her into the study of psychoanalysis and a lifelong examination of the psychological aspects of racism.

Global Racial Justice Meets Global Health

Stephens had long examined questions of racial justice. As dean of humanities at Rutgers in New Brunswick, a position she held from 2017–2020, she knew that other humanist scholars at the university also were researching these issues. But because the field of the humanities tends to reward individual research rather than group efforts, she says, there was relatively little collaborative work being done at the time. Her vision became that the Institute for the Study of Global Racial Justice would change that.

As Stephens began working on the institute’s launch – made possible by the support of Rutgers’ then newly appointed president, Jonathan Holloway, and a $15 million grant from the Mellon Foundation – she set out to make connections with other disciplines. She approached the university’s four chancellors, asking about who was producing research related to racial equity and social justice. Among those she was introduced to is Richard Marlink, the director of Rutgers Global Health Institute, which approaches its global health work through a health equity lens. Stephens soon joined with Marlink and colleagues to recruit global health faculty focused on issues of health equity, social justice, and population health; likewise, Rutgers Global Health Institute received a seed grant from the Institute for the Study of Global Racial Justice to initiate research related to decolonizing global health.

Mental Stress, COVID-19 Disparities, and Structural Racism

As her efforts to build the institute and cultivate diverse relationships continued, Stephens became involved with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation on a project related to the connections between race and health equity.

As a therapist, she’s witnessed these dynamics in many of her clients. “I see it in the mental stress produced in subjects who walk through the world with an unconscious defense against racial harm,” she says, “and in the pressured defensive structures of those from groups in the dominant racial majority who fear their only relationship to the history of race must be guilt and shame.”

She also recognizes that race-related health disparities have been magnified throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

“As scholars of race, we might have suspected that structural racism would have an impact on health equity, and nothing revealed that quite like COVID-19,” Stephens says. It was clear to her and many of her colleagues that social conditions contributed to the fact that people of color were particularly hard hit by COVID-19. For instance, they worked in larger numbers in many of the frontline industries that were more likely to expose workers to becoming infected with the virus. She also knew that the way the greater culture thinks about Black and brown bodies is a powerful factor in health disparities.

“Health,” she says, “is perhaps the most pointed area in which the discrimination against people who look different, who are perceived as somehow not human enough or not the standard human, has tangible impact.”

Uniting Interdisciplinary Perspectives

Black Bodies, Black Health is an outgrowth of that understanding. Cofounded with Enobong (Anna) Branch, Rutgers’ senior vice president of equity and a core faculty member of Rutgers Global Health Institute, the Black Bodies, Black Health project added two new sets of scholars – social scientists and biomedical researchers – to the Institute for the Study of Global Racial Justice’s original collective of humanists. Through seed grants, workshops, conferences, and both scholarly and public communication, the project has brought researchers together to engage in interdisciplinary work examining how structural racism impacts health outcomes.

From its inception in the spring of 2022 to its final roundtable earlier this month, the project’s wide-ranging efforts included research into communication between doctors and Black families in neonatal intensive care units at hospitals; a study on how racism contributes to psychological and physiological stress in Black athletes; initiatives studying the role of historical colonization on continuing health inequalities around the globe; and The Ramapough and the Ringwood Mines Superfund Site, an award-winning multimedia project co-created with members of the Ramapough Lunaape Nation Turtle Clan. Black Bodies, Black Health, says Stephens, “is one of our institute’s most significant signature projects, which I’m very proud of because it’s the furthest out from typical expectations for where a humanities institute would be.”

And yet, in its underpinnings in the belief that knowledge itself can be a powerful force to help reverse the damage wrought by racism, it’s very much in line with Stephens’s personal and scholarly conclusions about race.

“As a humanist,” she says, “I tend to believe that race profoundly shapes how we have come to think about being human, itself. Changing our racial attitudes requires getting comfortable with the idea that there are other humans in the world who live very differently than you do, and whom you may feel alienated from because of that very fact. Racial justice relies on a practice of learning how to be human together.”

– Leslie Garisto Pfaff