Special Feature: Rutgers Global Health Institute Seed Grants Series

Imagine that you’re struggling to breathe or you’ve suffered a fracture that’s broken through your skin, and you make your way to the hospital only to be told that the single surgeon on site is not trained to perform the procedure that could restore the quality of your life—or save it.

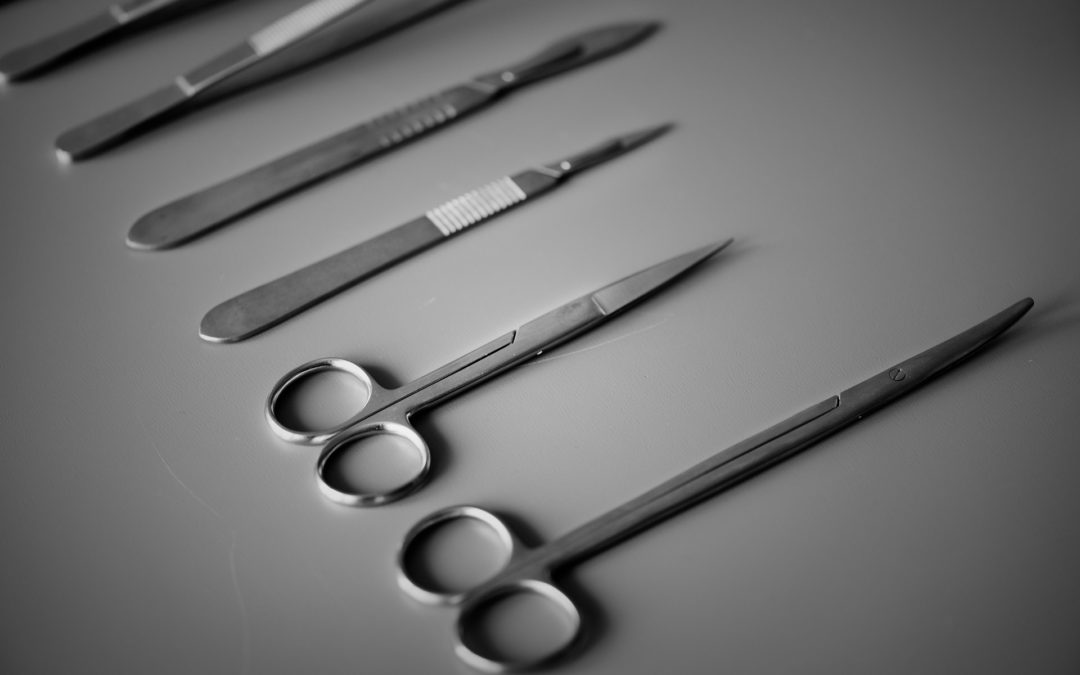

That’s the reality residents of rural Ghana are likely to face if they’ve had the bad luck to become injured or fall ill. Owing to a severe shortage of surgeons and surgical training in rural areas, many Ghanaians “have been suffering from their treatable conditions for years, struggling with pain, limited activity, inability to work, and complications due to lack of treatment of the original condition,” says Ziad Sifri, a core faculty member of Rutgers Global Health Institute and associate professor at Rutgers’ New Jersey Medical School (NJMS).

That shortage isn’t limited to Ghana, which is a West African nation about the size of the United Kingdom. According to a 2015 report from The Lancet medical journal, two-thirds of the global population lack access to safe and affordable surgery. In fact, the World Health Organization calls surgery, which can prevent premature death and disability, “the neglected component of primary care” and notes that it can “successfully treat a wide variety of conditions, from cancer and injuries to obstructed labor.”

Building capacity through distance education

Volunteer surgical missions around the world continue to make an impact, often being hailed as humanitarian success stories. And they are. But sending more surgeons, anesthesiologists, and nurses to communities in need is not a sustainable solution.

Ziad Sifri (left) and Harsh Sule are Rutgers Global Health Institute core faculty members and associate professors at Rutgers’ New Jersey Medical School.

At a rural hospital in Ghana, local clinicians collaborate with Rutgers faculty to fill the surgical gap. Funded in part by a seed grant from Rutgers Global Health Institute, Sifri and colleague Harsh Sule, a core faculty member of the institute and associate professor at NJMS, are developing a program to bridge the 5,000 miles between New Jersey and Ghana.

Since 2017, as part of Rutgers’ mission to extend its reach globally, the institute has awarded 10 such grants to faculty conducting collaborative, interdisciplinary activities designed to impact the health of communities in New Jersey and worldwide.

Sifri and Sule have used their grant funding to install the hardware necessary for a distance-learning program, implemented in 2018, with Ghana’s Tetteh Quarshie Memorial Hospital in the town of Mampong. Through this platform for continuing education and training that is open to all interested health providers, they are teaching surgical skills and diagnostic methods to help practitioners in Ghana overcome the constraints of understaffing.

The program extends beyond surgery (Sifri’s specialty) to emergency medicine (Sule’s). In fact, most rural hospitals in developing nations have no emergency department.

“Patients,” Sule says, “go directly to whatever department they decide they have an emergency in.”

At Tetteh Quarshie, an emergency room was constructed two years ago; now, physicians there are learning how to put the space to use.

Knowledge as a powerful tool

The distance-learning program, which allows providers in Ghana to participate in NJMS lectures and to suggest trainings in their particular areas of need, has been well received on both ends, evidenced by an increase in the number of personnel attending teaching sessions and Rutgers doctors volunteering their time as instructors.

If the new program is successful—an outcome being measured by number of lectures broadcast and attendees at those lectures—Sifri and Sule hope to replicate it elsewhere. There’s already been interest from other hospitals in Ghana and India.

The potential of these programs in resource-limited settings goes beyond skill-based capacity building. “Our thought,” Sule says, “is that the more knowledge we can provide the local personnel, the more they can demand improvement and resources within their own health systems.”

– Leslie Garisto Pfaff