Special Feature: Rutgers Global Health Institute Seed Grants Series

While there is no universal definition of the word, “culture” often refers to one’s deep-seated relationship with race, ethnicity, religion, language, gender, and countless other human dynamics.

Inarguably, culture influences every aspect of global health. It shapes how individuals perceive wellness, security, sexuality, disease, and suffering. Culture also can affect how entire societies structure their health systems, allocate resources, and respond to emergencies.

With all these complexities, how can we succeed in our pursuit of health equity?

Four tips for global health professionals on incorporating culture

Cultural competence—though no panacea for widespread disparity—is a critical skillset for individuals engaged in global health. Through decades of experience, a Rutgers School of Nursing faculty member has honed her own cultural competency, and she uses culture as a foundation for her research and capacity-building work in Latino communities.

Cultural competence—though no panacea for widespread disparity—is a critical skillset for individuals engaged in global health. Through decades of experience, a Rutgers School of Nursing faculty member has honed her own cultural competency, and she uses culture as a foundation for her research and capacity-building work in Latino communities.

Susan Caplan, assistant professor in the nursing science division, offers these practical tips on incorporating culture, which stem from her efforts to address mental health stigma among primary care health workers and patients in the Dominican Republic.

1. Learn what influences their worldview.

In the Dominican Republic, depression and anxiety are rarely treated until a person is severely ill and unable to perform daily activities. Though many factors contribute, Caplan explains one reason for this scenario: religious values.

Many Latinos are devout Christians, which often means that they believe in the potential healing power of religious faith, she says. “‘Have faith in God and pray,’ they might say. Or, they may believe that someone has a mental illness because he did not adhere to religious and cultural values. These values influence stigma and beliefs about mental illness, and they must be incorporated into our work.”

2. Remember: Doctors and nurses are people, too.

An authority on the assessment and treatment of mental health issues, particularly as they relate to Latino communities, Caplan focuses much of her work in the Dominican Republic, where she collaborates with the country’s Ministry of Public Health and University Autónoma de Santo Domingo. Her current projects relate to improving primary care providers’ abilities to address mental health with their patients.

“The doctors and nurses themselves,” she says, “may be dealing with their own personal mental health issues. They are members of the same communities as their patients, grappling with the same problems.”

Caplan’s perspective underscores that, with any global health outreach, cultural factors influence everyone involved, including professional partners. “That’s why we’re doing this,” Caplan says, referring to a training workshop she is conducting with support from a Rutgers Global Health Institute seed grant. “We are helping the providers develop communication skills and a comfort level for discussing depression and anxiety with their patients.”

3. Identify stigmas and how to navigate accordingly.

“A predominant stigmatizing belief is that depression is not an illness, that you need to just deal with it, or that you can snap out of it,” Caplan says. “These cultural values may inhibit people from coming to terms with their depression and talking openly with their health care providers.”

Her outreach will include teaching the doctors, nurses, and community health workers how to use motivational interviewing (MI), a patient-centered counseling style that explores, strengthens, and guides an individual’s motivation for change. Caplan notes that there is clinical evidence for incorporating MI into primary care in order to improve mental health.

This spring, Caplan will be leading a one-day seminar for 29 clinicians in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, which will be followed by two weeks of evaluation research using observational techniques. She hypothesizes that MI will be of value because of its ability to identify and mobilize patients’ intrinsic values, beliefs, and goals, “which will help both the doctors and patients work within—not against—the cultural values,” she says.

4. Look at your work through their eyes.

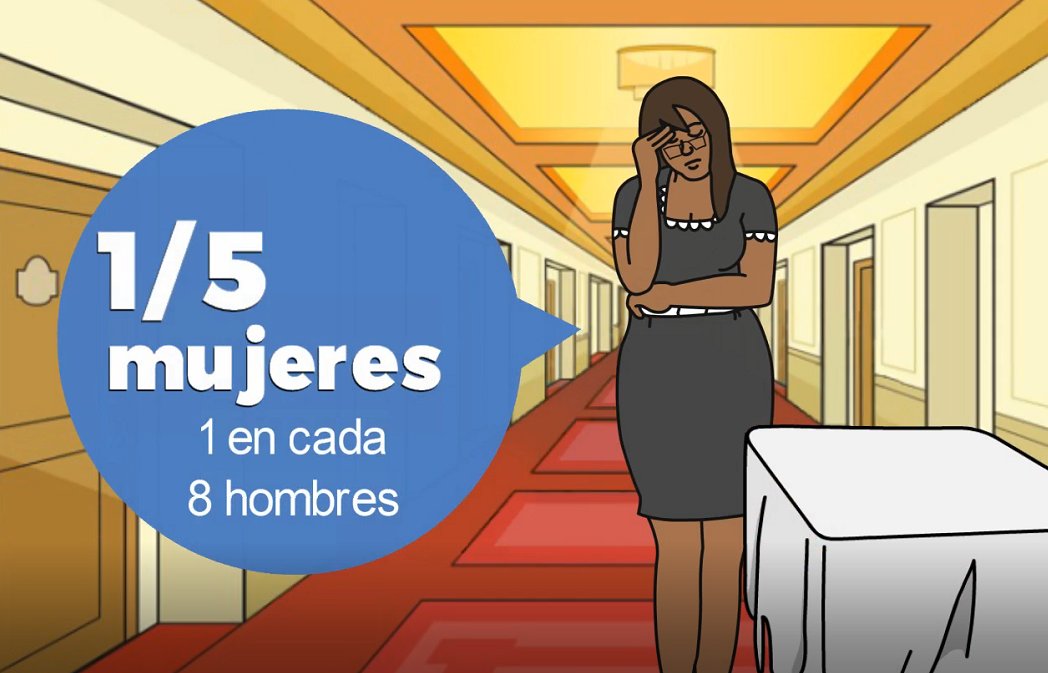

Caplan also is developing a smartphone app, with support from Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing, to help teach patients about mental and behavioral health. While working with an animation designer, she emphasized the need to depict scenarios that are culturally relevant for a Dominican patient population.

“One of the first drafts included light-skinned women working in corporate offices, and a nuclear family sitting around a dinner table in a stately home,” Caplan says. “But that’s not the reality of most people’s lives there.” Many women are domestic workers in private homes or service workers in hotels and restaurants, she explains, and the family dynamic includes many single mothers as well as grandparents, aunts, and uncles living together in relatively modest settings. “We had to go back to the drawing board, literally.”

By conducting focus groups, Caplan also received feedback about selecting a person to narrate the video content. “We need to consider things such as accent, inflection, and rate so that we can present the training materials authentically. The information is more likely to be embraced that way.” Students from University Autónoma de Santo Domingo provided the app’s voiceover narration, which was professionally recorded using studio time donated by the city’s public radio station, Los Centros Tecnológicos Comunitarios.